By James F. Downes (Visiting Scholar, European Union Academic Programme Hong Kong) and Chris Hanley (Senior Research Executive, TNS opinion)

Introduction

The Brexit vote on the 23rd June caused a political earthquake in British politics with Leave winning by 52% to 48%. Whilst negotiations between the European Union (EU) and the British Government are still ongoing as to when Brexit will be triggered and what it will look like, less is known about how perceptions towards membership of the EU have varied amongst the British public since the United Kingdom joined the EU in 1973.

Drawing on original polling data from the Eurobarometer, this article examines the attitudes of the British public towards membership of the EU from 1973-2016. The data is then broken down across decades in order to examine variations in support for the EU amongst the British public. The central argument of this article is that Britain has always been a ‘reluctant’ member of the EU, which we term ‘British Exceptionalism’. The article then outlines how the EU is currently embattled with three ‘existential’ crises and implications for the future of the EU.

‘The Reluctant Europeans’

From the start, Britain’s membership with the Europe[1] was controversial, both domestically and internationally amongst fellow European neighbours. The French President Charles de Gaulle frequently vetoed British membership throughout the 1960’s. The United Kingdom finally became a member of the EU in 1973 under Ted Heath’s Conservative Government with the Labour Party split on the issue.

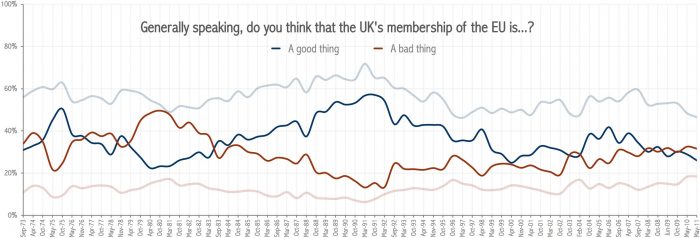

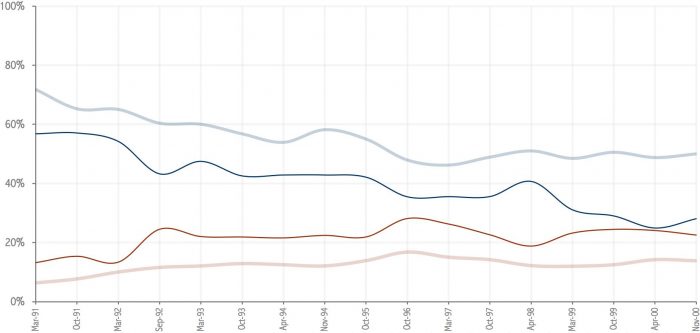

This article provides an overview of public perceptions amongst the British public towards the EU and draws on trend data from the Eurobarometer (conducted by TNS opinion) from 1973-2016 that allows us to investigate changes in public opinion across roughly each decade of membership (1973-1980, 1981-1990, post-1990, 2000 onwards). The question that we examine asks survey respondents the following: “Generally speaking, do you think the United Kingdom’s membership of the EU is a good or a bad thing?” This same question has been run from 1973-2011 and provides us with an uninterrupted trend series across time. The time series trend starts in September 1973 and is represented in Figure 1.1 below.

Legend

Each of the following trendlines within this article display the data in the same way. The dark blue and dark red lines represent the UK results for this question. The light blue and light red lines represent the average of all EU Member States. The EU Member States were of course asked about their own country’s membership of the EU.

Figure 1.1: Attitudes towards Britain’s Membership of the EU (1973-2011)

The early years (1973 – 1980)

The first period (1973-1980) shows the UK reaching its lowest result on record, hovering just above 20% at the end of the decade and suggests from the very start that the UK was a reluctant member of the EU. Yet this figure provides a stark contrast to the EU average line which is much more positive and shows general support for the EU project. In 1974, shortly after coming to office, Labour PM Harold Wilson promised to put the issue of EU membership to the British people in a Referendum. The final result was unanimously in favour of staying in, with 67% voting to stay in. However, shortly after the result, Figure 1.2 shows that the British public shifted to a much more pro-European stance on EU membership, which may be seen as a ‘poll bounce’ after the referendum result, but dipped significantly within the years 1975-1980.

Figure 1.2: Attitudes towards Britain’s Membership of the EU (Period 1: 1973-1980)

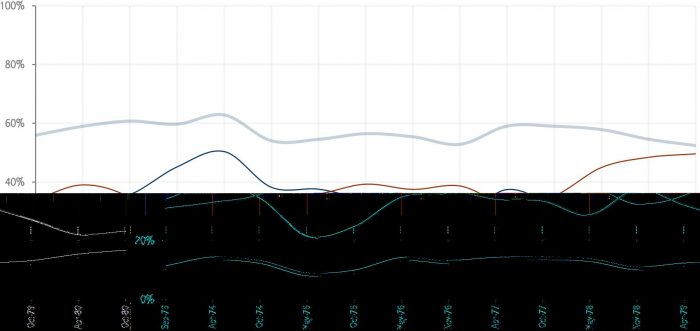

New hopes for the European project (1981 – 1990)

The 1980’s coincided with a dramatic shift in Conservative and Labour Party attitudes to Europe. Figure 1.3 breaks down perceptions amongst the British public from 1981-1990. During this period, the time trend in Figure 1.3 shows two key points. Firstly, the European outlook improved, with higher levels of support for the EU project.

Secondly, the EU and the UK witnessed a similar trend and shows support coalescing in public opinion. A key event during this period was Thatcher’s Bruges speech in 1988 in outlining a Eurosceptic vision of Europe, with the worry that the original vision of Europe as a trading area would be extended to ever more greater political and economic union. During the same period, Neil Kinnock’s Labour Party shifted towards from its Eurosceptic stance in the 1970’s towards supporting the European project. However, Kinnock would face increasing pressure from the left-wing section of the party.

Figure 1.3: Attitudes towards Britain’s Membership of the EU (Period 2: 1981-1990)

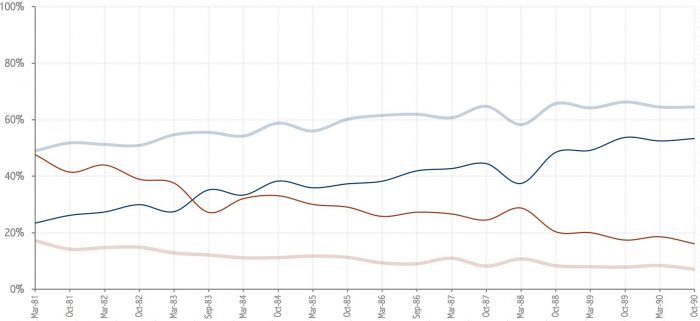

Post-1990’s slump

Figure 1.4 shows a peak in EU optimism in the 1990’s and how this period was met with a steady decline in public opinion, both across the EU and is particularly pronounced in the UK. Events in this period proved to be tumultuous with Thatcher’s downfall and the European Exchange Rate mechanism collapse in 1992, alongside the creation of the modern day EU from the Maastricht Treaty. During this period John Major’s Government faced frequent division over Europe with a number of Eurosceptic cabinet members such as Michael Portillo and John Redwood voicing their dissent. At the same time, Tony Blair’s rebranding of New Labour coincided with the party committing itself to the EU and the prospect of greater integration and enlargement in the future.

Figure 1.4: Attitudes towards Britain’s Membership of the EU (Period 3: 1981-1990)

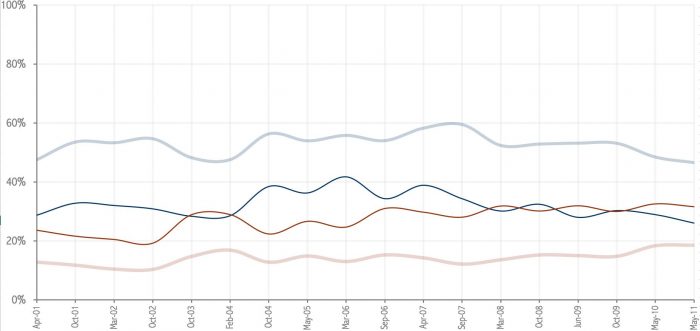

Brexit beats recovery (2000-2016)

The millennial period saw a slight recovery in the public perception surrounding the UK’s place in the EU and figure 1.5 depicts this relationship. The ‘90’s witnessed the public’s positive perception of EU membership spiral downwards from around the 60% mark to 30%. This began to level off around the same time that Blair took office but by 2003, two years after his re-election to office, negative perceptions overtook the positive perceptions. To provide some perspective, the general view of EU membership amongst the public had been more positive than negative for the previous 20 years (since 1983).

When Gordon Brown took office in 2007 this was shortly met with one of the largest financial crises Europe had seen – this unsurprisingly was a big blow for the European project. The end of the decade saw Euroscepticism on top, reigniting the Eurosceptic wing within the Conservative party as well as giving momentum and much needed credibility to the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), which gained significant traction in national and European Parliament elections.

Figure 1.5: Attitudes towards Britain’s Membership of the EU (Period 4: 2001-2011)

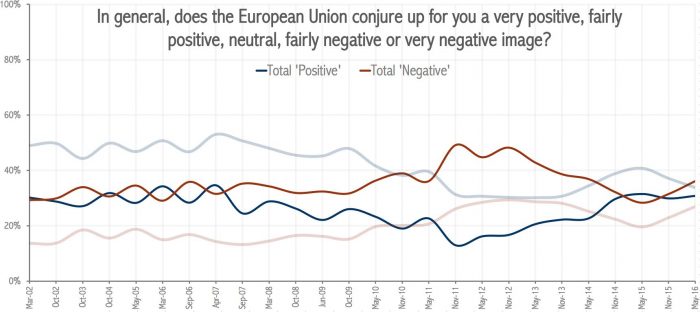

Unfortunately, the question about EU membership ceased to be fielded from 2011 onwards so we turned to a new question which gauges the general sentiment in a similar way. The question asked whether the EU conjured up a positive or a negative opinion for respondents. There was also a ‘neutral’ option but for the sake of clarity, this is not presented in the final trendline.

Figure 1.6 shows that the UK trailed behind the overall EU trend in terms of sentiment but that the British public reacted in a much more negative way in 2011, a year which saw many countries re-enter recession, as well as disputes around various bailout packages. David Cameron assumed office in 2010 and arguably used the gradual recovery of the British economy against the backdrop of the failing European economy as a reason for offering the British public a referendum on the EU. This eventually became part of his platform in 2015 to appease the Eurosceptics inside his own party and seek to ameliorate the threat of UKIP’s advance on the EU issue.

Whilst the 2015 general election provided the Conservatives with a landslide victory over the Labour party and as part of his pledge, a referendum on the EU was put to the British public. And for the first time in history, British and European opinion alike seemed to have converged in their view of the EU. Although figure 1.6 seems to suggest that British public opinion appeared to improve in the final months, years and years of ingrained British Euroscepticism eventually prevailed on 23rd June. Evidently, Britain has always been a ‘reluctant’ member of the EU and this phenomenon can be viewed as ‘British Exceptionalism’.

It is fundamentally clear that politicians on both the left and right of British politics have failed to recognize the long-term impact of British Euroscepticism amongst the British public. To borrow a theory from the political scientists Matthew Goodwin and Robert Ford, a large segment of people who voted for Brexit constituted the ‘left behind’ in society amidst core issues such as immigration. However, a large proportion of people that voted for Brexit were also committed Eurosceptics and sought to take back control. We argue that politicians are in denial if they think that Brexit was a flash in the pan event. We are living in a ‘new form of politics’, not just in Britain, but in Europe more broadly. The relationship between elected representatives and voters has evolved and politicians are now under increasing scrutiny to stand up and deliver on their election promises. The next two years will be key in British politics and also for the future of the EU.

Figure 1.6: Attitudes towards the EU in general (2002-2016)

Conclusion

Whilst debates over what Brexit will look like and when Article 50 will be triggered are likely to dominate the next two years of British politics, the EU is currently facing a triple ‘existential’ crisis. Brexit constitutes the first ‘existential’ crisis, with the ongoing refugee crisis and disputes amongst EU member states in resolving the situation. Thirdly and most significantly, the third crisis is political and constitutes a sharp decline in trust across European democracies towards the EU. Populist far right parties such as Alternative for Germany (AfD) and the Front National in France have weaved a narrative of political discontent through opposition towards immigration and anti-immigrant sentiment, alongside ‘hard’ Euroscepticism that has seen increased prominence of late. With next year’s German and French parliamentary elections on the horizon and the resurgence of far right populism, we are currently living in a ‘new form of politics’. Most significantly, how the EU manages and responds to these events is likely to determine its future.

[1] The European Union in its earliest form was known as the European Economic Community (EEC) and can be seen as a precursor to the European Union which incorporated the European Communities in 1993.